In the Bag: Micheal Do

Curator, programmer and writer, Micheal Do with his Georgie Bag.

Micheal Do is a curator, programmer, and writer who has emerged as an integral presence of the Australasian contemporary art scene. In his role as Curator of Contemporary Art at the Sydney Opera House, his work with artists and institutions steers the intersection between the past and the present for public consumption. Read on for our conversation exploring Micheal’s spirited pursuit of creative nourishment, his exploration of curatorial practice, and the role of art in making sense of the world around us.

Career

Yu Mei: How did the trajectory of your career as a curator unfold?

Micheal Do: How did I get here? Life is so rhizomatic and accidental. I don’t think I intentionally set out to be a contemporary art curator. I studied art history and law. People often joke that when kids do double degrees, one is for them, and one is for their parents. So, art history was for me and law was for my parents.

During university I was just having a real riot—enjoying myself, learning, partying… all the things that you do as an undergraduate. I got talking to my friends and they said, “Oh, we’re doing these internships” and I thought, “Oh my god, what is an internship? How do I get one?” So then set about searching, Googling and applying and one thing led to another. From these internships, I discovered that I had a knack for working for artists. My entry into the museum was not curatorial, it was in public program and audience. I believe in the power of art and what art museums can do for people. So, through that North Star, I got to where I am today. None of it was intentional, but everything happened as it should have happened.

YM: What university did you go to?

MD: I went to University of New South Wales and College of Fine Arts and Sydney College of the Arts.

YM: Did the law degree help you navigate public programming? Do you think it gave you a different perspective?

MD: Yeah. Law and contemporary art have so many similarities and overlaps. I think the thing which drew me to those industries was the sense of curiosity that you’d have to have to be a successful lawyer or a successful artist. The best artists I know are completely obsessed. They are greyhounds when it comes to their practice and in trying to interrogate an idea and figure out an outcome. You could describe many lawyers similarly.

Of course, the law is often not solely about the law itself. It’s about conflict; it’s about when things go awry. Law serves as one prism, one lens through which to view these issues. Similarly, contemporary art is not often about the practice of art-making aesthetics itself. It is about the world around us; trying to make sense of happenings, ideas, history, and that is just one lens to view it. So, I think there are so many more similarities to both these industries than what people might naturally think.

YM: Legal writing is fascinating, it’s an art if you can do it well. Has that skill played into your ability to make sense of the comments on society and the stories artists are trying to tell?

MD: One hundred percent. You can explain the most complex ideas in the simplest ways.

YM: When did you move into curating?

MD: Sometimes it’s being in the right place at the right time. I was lucky enough to be invited to curate a show at the museum where I was working, Casula Powerhouse, which is an incredible industrial space converted into an art centre. Off the back of that show, I was invited to do another. That show toured fourteen regional galleries around Australia.

I think great curators use the language of “we, how, why?” They’re in service to artists, ideas and culture. That is the energy that I brought to my work and people could see that. I find it difficult to analyze it too much because it just kind of happened. None of it was intentional, but I think having an open heart and open mind is what has kept me in good stead.

YM: Has having a service-driven mentality and the desire to support creatives and artists always been part of your makeup? Where do you think that came from?

MD: I think it comes from curiosity. I need to be nourished at all times, whether that is visually, gastronomically, auditorially, or physically. When you have that as a guiding force, you want to enable the nourishment of others.

YM: A give and take. When you were young, was there an exhibition or a piece of work that was formative for you?

MD: I don’t have a defining moment where I saw the light and thought, “This is the career for me,” but I had moments where I knew I needed to stay in this career. Most recently, I saw William Kentridge’s chamber opera, Waiting for the Sibyl, which was an incredible piece that drew in native African languages including Zulu, Setswana, Sesotho, and Xhosa. It was a dreamscape of colours, textures, and stagecraft, with such incredible musicianship. I saw it and was speechless.

Another was when I was recently at CARA, the Center for Art Research and Alliances, in New York, and saw a beautiful performance work by Berlin-based artist, Ligia Lewis. I was so moved that I had to leave the room.

So, I didn’t have one moment that drew me in, but I’m always looking for moments which overwhelm and fill me up with something. That’s why I do what I do. I’m always trying to reach that as a destination for myself, the artists, the audiences, and the public.

YM: That physical response is something else, isn’t it? You have touched upon what drives you, and there are evident common threads throughout your work. Can you tell us about your curatorial approach? Is there a certain framework that guides you in your collaboration with the artists? Does that change if it is a solo or group show, or whether it is with an institution?

MD: There are so many invisible forces that shape the show outside of the curatorial intent. And, in many ways, I’m subject to them too. But I’m in a fortunate position in my life and my career that I get to choose the artists that I work with who shape what my curatorial output is. Not all curators have that. What is foundational to me is ensuring that contemporary art is always about its time. It’s about reflecting the zeitgeist. I think of myself as a translator in that way, an enabler.

What is key is finding artists who can translate the moment into something more complex. It starts with the right artists, with the right practice, at the right time. It’s hard to articulate further because, otherwise, it’s giving away trade secrets.

YM: From a logistical perspective, what are the mechanisms you are working with? Do you have the luxury of longer lead times? You’re often balancing many aspects of various projects at once.

MD: The contemporary art program with the Sydney Opera House is a big performance program which includes looking after the lighting of the sails, which is a large projection mapping project on the house every year, in addition to artists’ talks, and installations—we’ve just recently accomplished an amazing temporary public artwork. Each of these programming outcomes requires a different skill set and artists to fulfil that brief.

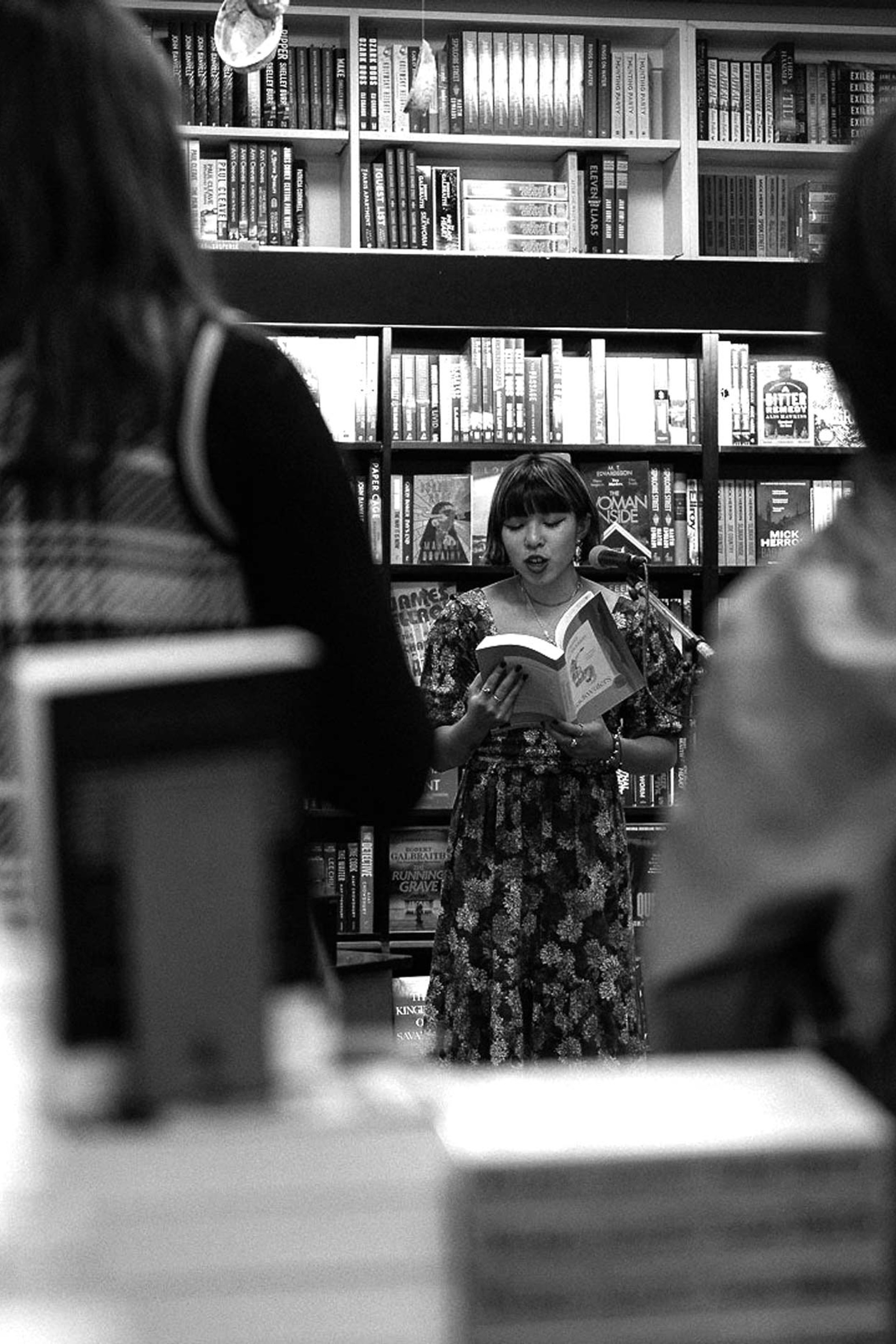

I guess to answer your question, I work like an artist. I don’t clock on at nine o’clock and off at five. The things I do in my spare time are all about culture, and that might not necessarily be visual culture—I might go to a concert, the theatre, a reading, or whatever. It’s about trying to absorb what the critical thinkers are thinking, asking, and saying about our time. Going through that process of trying to nourish myself with that information, you meet people along the way that you think, “Wow, this person’s doing something, this person is saying something.”

So I have a list of artists who I admire and want to work with. The core of what I do is finding the right time and opportunity, because the artists that are interesting and defining a moment rise to the top but, you’ve got to match them with the right context to achieve a wonderful outcome. I’m fortunate enough to work with such an iconic building that many of the artists that I meet have an idea for it ready to go, which is a great thing but also such a curse because they come in with that.

YM: That preconceived idea?

MD: Yeah.

YM: It’s a big undertaking. Do you feel a significant amount of pressure and responsibility?

MD: Absolutely. I take my job very seriously, and it is a big responsibility. The thing I haven’t talked about is ’saying no’. I frame the curator as someone who enables outcomes, but equally, they are someone who says, “That is not a priority,” or “That is not of the time.”

YM: That’s such a good point. When you’re working in a way that involves commenting on a period of time, you can run the risk of getting caught up in creative trends or other social commentary trends. It takes discipline to discern what are the most meaningful aspects to work with.

MD: It’s hard because, as humans, we have our personal tastes, and then I have my public curator tastes as well. When trying to reconcile these, there is often a tension because I’ll think of an idea, or I’ll have an artist who I love and want in my home, but they might not necessarily make sense for public consumption. So, it’s about having to separate the two and then being analytical about them as well.

YM: It sounds like you’re fully immersing yourself at all times. You must have access to an amazing library and archives. Are there any particular methods that you have that help facilitate your research?

MD: You have to know your art history; that is 101 of curating. As curators, we are translators, linking the past to the present. To make sense of now, you have to know what’s gone before. I love referring to archives, books, periodicals, and magazines from years ago because you’re discovering where an artist’s work comes from. But, equally, you can’t be locked into the past or held hostage to the past by the past.

Having a strong peer cohort where you can bounce ideas off is also very important, and that being a global peer cohort. Because, while Australia and New Zealand hold their own, and are just as powerful as any other country, making sure you’re connected to other places of culture is important because we shouldn’t be siloed, we need to have a global conversation.

YM: Yeah, absolutely. The show you recently worked on at the Sydney Opera House—the public artwork you mentioned earlier by Quandamooka artist Megan Cope—looked incredible. It must have been quite a physical undertaking (made up of 85,000 oyster shells) and certainly took the installation out into the world. Can you tell us about that project and how the physical venue of your shows intersects with the work itself?

MD: It’s a project that Megan and I are immensely proud of. At its core, it is a temporary public artwork, but at the same time, it’s a social practice work. To prepare the artwork in the main material, oyster shells, we held over 100 workshops in three locations, asking the public to help assist in preparing them. In doing so, they were connected socially; they met strangers, and we had conversations about the importance of voices, the importance of waterways and the environment.

Then there’s the sculpture itself, made of Kinyingarra Guwinyanba poles, which are large poles with nests of oyster shells on them. Megan intends to plant them in intertidal zones, where oyster reefs might have existed but have now been made extinct. The power of bivalvia and molasses is that they cleanse the water, so the work is a tool to rehabilitate our waterways. Another aspect is that they love growing on other oyster shells, so they grow on their ancestors in that way. It is all wrapped up in this incredible sense of storytelling because, before the Western occupation of Australia, all along the Sydney Harbour shore were these mounds of discarded seafood, which were evidence of meeting places, hunting places and gathering places for our Aboriginal people. The work has a deep environmental care and is all wrapped up in an Indigenous worldview of togetherness and sharing, and of taking that back to the earth.

YM: It’s quite remarkable. This is a great example of a work interacting with its environment. Has this been something you’ve navigated with other shows? How does space influence your thinking and approach to the work?

MD: I think an aesthetic consideration is as important as the social-political and conceptual considerations of any artwork. You always have to make sure that visually an artwork works in a particular space because that gives it its power. In many other exhibitions, I’ve invited artists to respond to a specific space. I’ll give a provocation and they’ll respond.

YM: The space can give a lot of freedom to artists as well. For example, the story of the opening of Dia Beacon, in New York, and how it was a revelation as it was the first time some of these artists could work on pieces that were so monumentally huge.

MD: Dia is one of my favourite art organizations in the world. It’s how I love experiencing art—when you can be alone and just luxuriate. Donald Judd was one of the kind of key figures of the Dia generation and is a big proponent of their permanent installation. It’s the perfect marriage of the artwork and the context so that they’re considered as one. I think there’s something positive to be said about that.

Micheal at home in his Gufram Pratone Chair, designed in 1971 by Ceretti, Derossi & Rosso

Life and Utility

YM: What is a typical day for you? What is your routine?

MD: Every good day begins with a coffee. I’m someone who loves to be in the office or out at artists’ studios. Home, for me, is a place of entertainment, a place of gathering and relaxing. I like to be out of the house, in the world, to do my work with a coffee.

YM: Has there been a lesson that you’ve learned that has informed the way you look at the world?

MD: Something I take into all spheres of my life is knowing when to arrive and when to leave.

YM: That’s a great one.

MD: It’s how you get through life as unscathed as possible.

YM: And goes back to the value of time that you mentioned earlier. How would you describe your style, whether that is your wardrobe or the design pieces you surround yourself with?

MD: My style is functional but thoughtful. I love clothes, makers, and designers who are thoughtful in their approach. I’m always looking for things with intelligence, with a twist. I want something that elicits some contemplation. A sweater is never just a sweater—it needs to function as such, but also do a little bit more.

YM: Give us an example.

MD: I love the work of Daniel Lee who is the Creative Director at Burberry, previously at Bottega Veneta. He plays with those house codes of English style. I’m not into slogans and labels. I love when designers think of themselves as artisans and people who can play with the language of a garment, as opposed to just slapping a logo on.

Raf Simons is someone whose work I worship at his namesake brand and also at Prada. He is a designer who draws in music, photography, and artists into his practice. I love it when clothes refer to something more than themselves. I guess this fits my worldview that contemporary art is one lens to view the world, as I demand my clothing to be a lens to view the world as well. But it needs to also be functional.

YM: Everything Raf has done with the artist and long-term collaborator, Sterling Ruby, is a brilliant example of that. We have heard that you are skilled at piecing together your interior space—with design pieces paired with furniture of unknown provenance.

MD: The older I get the more intrigued I am by artists experimenting in furniture making. It’s funny, in our living room we have lots of chairs, but few of them actually look like a chair. I love furniture that evades definition and expectation. But equally, I love things that have shaped history.

My sense of furniture is about linking the past to the present; benchmarking the Masters with people who are emerging as well. Having your interior world be an extension of your exterior world is interesting to me. I’m trying to create that sense of questioning, of wonderment, of curiosity. So the makers we have, that I surround myself with, must have that at their core.

YM: Do you tend to get fixated on a piece or are you quite fluid in what you’re curating within your own space?

MD: I try to move through life trying to not curate, I’m trying to not acquire anything. There will be moments when things, ideas, and artists haunt me and I can’t get them out of my mind. That is when I think “I have to have more of this.” Of course, there are things in your life you come across that you’re happy to just appreciate its existence in a museum somewhere, and there are some things that you think, “I have to own that, how am I going to make it happen?”

YM: Is there anyone or anything haunting you at the moment?

MD: There are too many to list. Places I want to revisit and travel to, artists’ works that I’m so desperate to have, to pieces of clothing that I would love to have. There’s always a list. There are always things that are haunting me, but it’s about how long they’ve haunted me.

Equally, my partner has a great piece of advice that he reminds me of often. It is that you can have everything that you want in life but you just can’t have it all at once. I’m a big believer in timing and Erykah Badu has this very sage phrase, “If it’s meant to be yours, you will have it.” So, I kind of roll with that.

YM: It’s true. You can do it all, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you do it all at the same time. To do it you often have to compromise something, at some point, and it then ebbs and flows.

MD: Life is long. We live in this age of click-and-collect when we have an entire lifetime to think, to plan, to acquire. To know and unknow.

YM: The slowness of discovery can be such a crucial part as well. The immediacy that we have all got into can be detrimental at times.

MD: Yeah. I always try to resist impulse shopping. I resist impulse curating, I resist impulse eating. You have to resist this desire for now and think, “How does this all make sense?”

YM: It sounds like you have great discipline.

MD: I’m not saying it’s 100% achieved, but it’s certainly the aspiration.

YM: What do you do to unwind? What makes you feel most confident?

MD: I recently saw a talk with Jennifer Coolidge and she had this wonderful bit of advice for any artists or actors out there: go see really bad things. Anything you hear of that is terrible… go see it. Because you immediately feel much better about yourself as a maker or producer.

I tend to be quite harsh on myself, nitpicking about what I do and how I do it. Taking a step back and realizing that the world is a much bigger place, and understanding the true stakes is important to give myself that boost.

To feel energized it comes back to the notion of nourishing. I want to listen to great music, I want to visit great places, and I want to experience things that move me. That’s why I’m so fortunate to be a curator.

YM: Does that mindset apply to your interactions with people? Such a significant part of what you do is working with artists, and the people around the work. Do you also get filled up by social interactions?

MD: No, I’m an introvert who has to do extroverted things, so I spend a lot of time by myself. One thing I love doing is going to museums, concerts, or films by myself. Those moments fill me up.

The other thing I love is discovering things that are new to me. They might have been centuries old, or you might have lots of scholars who are deeply engaged with that thing, but to discover it for the first time, and experience the richness of it, these are the things I'm always hoping and looking for. That’s why travelling around the world to go to new museums or to festivals is a big part of my practice as well.

YM: How much of your year are you travelling?

MD: This year has been quite an exceptional one. I’ve been away a lot. I’ve just come back from a three-week residency at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

YM: What was that for?

MD: It was for a professional development residency where I got to be a fly on the wall and meet many great artists and curators. It was a fertile and testing time; landing in a place where you don’t have much context to who you are, and you have to articulate what you’re about and what you believe in.

YM: That must have been quite an experience.

MD: New York is a demanding place; you have to have to give it your all. Also, New Yorkers are very much like the stereotype. It’s good to be amongst that energy.

YM: Did you experience any significant differences in their approach or point of view? What have you taken back to Australia?

MD: The thread that stands out the most is the importance of the invisible work. As curators, we want our work to be public, but there is a lot of invisible labour that goes into developing, be it rallying together, building communities, or having conversations to try to align ourselves as an industry. That is the work that I’m going to be focusing on.

YM: Are you naturally an organized person or is it something you have to think about?

MD: I think organization is a skill you learn with time. For many millennials, the concept of a side hustle is very common, so when you’re trying to bridge or make it work, you need to be organized. You need to know when things are due. What you can take on, what you can’t take on. That is, I think, the basic tenet of being an adult.

So, there are two things that I do as part of my organization. The first one is that everything goes on the calendar. If it is not in the calendar, it does not exist to me, and I’m very open to people about this. The second thing is a lesson which I’ve learned: efficient people do things immediately. They say, “I’m going to send something to you” and send it now. I’m not saying that for things that need deep thought and contemplation, but for administrative tasks or things that you need to do, do them now.

YM: Don’t overthink it.

MD: Yeah.

YM: You are out of the house for your work day. What are you carrying? What are your essentials?

MD: During the day I will always be carrying my AirPod Pros. I am always listening to music, an audiobook, a YouTube video, or something. It is powerful to be able to create your environment through what is quite a modest thing, and I love to be insulated from the real world or in another world. I will also have my notepad—I need to write things down. My notes are always large and expressionistic with lots of boxes and mind maps, trying to make sense of things.

YM: Do you have a particular notebook?

MD: Yeah, it’s an artist pad. I like to use at least 220 GSM, and always with a Blackwing pencil. I never write in pen for my notes, only when I need to write a card or something that’s forever. I’ll also always have my phone with me... that’s a given. And really, that’s it. My credit card. Those are my essentials.

YM: What about when you’re travelling? Do you have any packing routines or tips?

MD: I will always have a copy of the Financial Times and The New York Times—nothing beats a hard copy. I also love to take a small scented candle with me, tea tree oil, and my Lucas Papaw, because travelling dries you out.

YM: Do you have a particular scent for your travel candle?

MD: I love the Cire Trudon. I think it’s the Abd El Kader.

YM: Do you have a uniform that you pack?

MD: I always take more than what I need, which is not necessarily a good thing or something that I would recommend. But my travelling staples always consist of Prada Re-Nylon. I love systems and that is a fantastic system that you can add to over time and is adaptable to any climate, any place, and no ironing is needed (which is essential). And, of course, overhead earphones for the plane.

YM: Fantastic. The concept of building systems has played an integral role in the development of Yu Mei’s ranges; the design and utility of the pieces themselves, and also how they fit together.

MD: I admire designers and businesswomen, business people, and Jessie (Wong) is part of that list. She is a thoughtful designer who is always thinking about her customers and what they need. I take such inspiration from someone who works hard and demands a lot from their goods. Someone who does not want to compromise on style or design. In many ways, I’m aligned with that thinking: yes, I have to be on the go, yes, I’ve got to do these things, but I want them to work just right. And I want to move from day to night, from the weekday to the weekend, and have it just work.

I’m minimal in my thinking and philosophy on life. I’m searching for the perfect thing. My ideal life is if I just had the one perfect thing of everything. The one place I get my coffee, the one blend, in the one mug that I’ll drink from. The one type of clothing that I’m wearing, the one phone, the one headphone, the one author, the one theatre. It’s not necessarily about the most expensive thing or anything like that. It’s about finding the thing where the person is doing the perfect expression of it.

YM: It’s great to be so thoughtful in the experience you’re creating for yourself.

MD: I’m always conscious of discovering more about the supply chain. It’s about eliminating things that have very short shelf lives. I want to be able to reuse, and reuse, and reuse. I believe less in the bamboo compostable plate and more in a ceramic plate that has been ethically made that I can use forever or gift to someone.

YM: Everything you have said ties back into what you do in terms of being vigilant as to the state of the world, whether that’s on a basic human level or greater. What is your perception of the industry at the moment? Where do you see it going in the immediate future?

MD: That’s a big question. I think we’re still feeling the impacts of Covid-19. Economically, the policies that were implemented during that time are having run-on effects in politics, the economy, and culture. It has played a big part in influencing these major political schisms, and issues, and wars that are happening. So this moment in time feels depressing or particularly difficult, and that has certainly impacted a lot of art-making and a lot of artists. Certainly, the funding climate is not amazing, the collecting climate is not amazing, the audience base is not amazing, and not what it once was. A lot of these things stemmed from that major event.

Similarly, my work now is about rebuilding, rehabilitating, and doing that invisible culture-building work in the background to strengthen their silience on the part of culture and ideas, and to make sure that we don’t lose that because in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, when there’s warfare and famine, and those basics and essentials of needs are not met, culture and ideas can be pushed to the bottom of the list. Of course, artists are not immune from these social interruptions and issues, so we need to look after them and ensure they can contribute to society through their art.

YM: The notion of public funding for the industry is also changing, so roles within the industry, like curators etc., are having to step up to make sure that nurturing is happening in other ways.

Micheal's furniture collection includes pieces by Achille Castiglioni, Max Lamb, the Campana brothers, Superstudio, Gaetano Pesce, and Xu Zhen

Recommendations

YM: Which exhibitions coming up this year would you recommend we keep on our radar?

MD: My colleague at MoMA is working on a large Joan Jonas exhibition which I will 100% be attending. Joan Jonas is one of the art world’s mothers to many artists. She is a legend, and to see her work contextualized in the way that Anna Janevski is doing will be very exciting.

YM: Who are you inspired by?

MD: There are too many people to list. But currently, there are two things: the book I am reading is Orlando by Virginia Wolf, because the incredible filmmaker and queer theorist, Paul Preciado, has made a film adaptation, and before I watch it I want to refer to the original text again. That’s this week’s project. The other thing is I’ve just recently gotten into audiobooks. I appreciate the height of the audio craze was during the pandemic, but I’ve only just gotten on the bandwagon.

My latest audiobook project is learning more about the icons, the divas. I’ve finished the Britney Spears and Mariah Carey autobiographies, and now I’m onto Barbara Streisand’s. I’m interested in divaship as a practice, and also the stories of these kinds of women; they have been held under the thumb of the patriarchy and they’ve managed to find a trapdoor to escape and build these huge lives using their raw talent, nerve, luck, and struggle to come out on top.

YM: Fun to do them back-to-back.

MD: I love a project. YM: Michelle Williams is reading Britney’s, isn’t she?

MD: Yeah, she’s done an amazing job. I was a bit sceptical at first, but there’s no separating her and Britney’s voice or persona as you’re listening to the book, you feel as if she is the one and the same.

We all need a bit more divaship in our lives, and why not learn from the best?

Bag 0

Duties and taxes included for Australia and New Zealand

Carbon Neutral Shipping

Shipping

| New Zealand | Complimentary Shipping over $50 NZD, Complimentary Returns, Click & Collect |

| Australia | Complimentary Shipping over $200 AUD |

| Rest of World | Complimentary Worldwide Shipping over $200 USD |

Areas

| New Zealand | Orders shipped within 2-3 working days, sent via tracked Courier Post. |

| Australia | Orders shipped within 2-3 working days, sent via tracked DHL Express |

| Rest of World | Orders shipped within 2-3 working days, sent via tracked DHL Express |

New Zealand and Australia

Taxes and duties are included within the purchase price.

Rest of World

As orders are shipped from our New Zealand warehouse you may incur duties, clearance fees or local taxes. Yu Mei Ltd does not cover these charges and is not liable for any fees incurred; although we will always do our very best to ensure a smooth delivery to you. For more information, we advise you to check with your local customs agent.

Choose Your Shipping Region / Currency

Change Region / Currency

Join

Club Yu Mei

Club Yu Mei is a community of like minded, forward thinking individuals. It’s a place to celebrate those who inspire the Yu Mei brand and beyond. From interviews and ideas to events, debates, dinner parties and more, the Club is an inclusive space by real people, for real people. Unlock our cabinet de curiosités and discover the thought-provoking universe of Club Yu Mei.

Search

Popular Searches

Choose Your Shipping Region / Currency

By continuing to use this site you consent with our cookie policy.

To stay abreast of all things Yu Mei, join our Club newsletter and enjoy 10% off your first purchase.